Odesia por el Laberinto:

Journey of the soul to the New World

Corelyn F. Senn (2002)

“Labyrinths are allegories for journeys representing ventures across time and space, from This World to the Otherworld and back”

Sofia Guerra

The journey of the soul beings already tainted by sin. According to Catholic doctrine sin entered the earthly world through the actions of one human, and we bare the responsibility for the disobedience of Adam’s second wife as the following generations (Roman 7:9-11).

The second half of the 15th century brought political changes to Spain that would eventually domino into radical historical, political, and religious changes that we see in effect to this day. The marriage between Castilian heiress and Aragon heir, Isabella and Ferdinand II, in 1469 unified the two predominately powerful Catholic kingdoms occupying what is drawn with modern boarders as “España” . Note: this was not a marriage of love, it was essentially a power move.

The Kingdom of Spain now held one of the largest military fronts of in the developing Western world. The unification of the two largest regional powers during an era wrought with violence and conversion flavored the next two centuries for Europe, and the Americas. The spirit of crusader conquest had received its ‘second wind’ later in the previous century. The Holy Office of the Inquisition was founded in 1478.

For centuries prior to the official founding of the Inquisition, Spain had been a multi-religious land. Tensions over land between Moores, Jews, and Catholics accumulated between the 8th and 15th century. The Moores were pushed out with the fall of Granada in 1492. While there were some converts among the marginalized religious populations, the Catholics Monarchs lacked tolerance for this behavior deeming converts illegitimate Catholics due to their lack of ‘blood-purity.’

Conversion and conquest would become the dominate message emanating from the Kingdom of Spain entering the 16th century. Multiplicity within Spanish Catholicism mimicked the past religious diversity of the Iberian peninsula, including its instability. The Catholic message of the country was far from unified. However, the newly dominating Catholic Monarchs were essentially a medieval superpower. With an enormous military front and the backing of the Roman Catholic Church, Isabella and Ferdinand II moved forward with the Inquisition.

Architectural Styles

The architectural style of Medieval Spain encompassed predominate European traditions. Histories of great medieval Italian basilicas paved the ground work for a Spanish counterpart. Romanesque and Gothic flavored freestanding sculptures punctuate the grand spaces. Simple bright light walls tied in luminescent Gothic architecture, yet it was distinctly flavored by its Moorish occupants.

From the West, Spain uses the traditional cross-shaped floor plan. This was, and still is the cannon for construction of Cathedrals across Europe and the world after its medieval conception. Vaulted ceilings, sculptural door jams, and catholic narratives typically dress the Cathedrals. Biblical stories are brought to life as Christ’s passions are depicted through frescos covering the walls. The artists tasked with adorning the Cathedrals walls did not shy away from the brutality Christ faced in his pious trials. The aim was to essentially ‘move’ individuals spiritually through intimidation tactics and a running narrative. Gothic traditions of a bright white luminescence work to literally light up the place, but also evoke the symbology of the color. White evokes purity in spirituality; the simplicity of the hue promote penance without distraction from over-ornamentation.

From the From the East-Moorish and beyond- the Spanish heavily borrow a variety of arch shapes and designs, as well as different forms of ornamentation from the same group they spend hundreds of years pushing out of the Iberian peninsula. Ogee, and lancet arches had long been appropriated by the Spanish which distinguish their style from other European styles. Voussoir arch ways, which were not original to Moorish architecture, yet regularly and incredibly used, became a staple in masterpieces like the baths at Albambra de Giralda. Rather than following in strict adherence to the Italian tradition of heavy sculptural reliefs on the door jams and archivolts, the Spanish used those surfaces as opportunities to employ the intricately precise geometric designs, and similarly designed coffers and corbels to show divinity. The Moorish and Western European elements are so well integrated that it becomes an architectural flavor that is distinct to the Iberian Peninsula.

Cathedrals in the New World

The first Cathedrals in the New World were put up as symbols of power from the missions sent through the Spanish Inquisition. They became institutions of conversion, education, and exploitation. The first monks of the Franciscan order reached New Spain early in the 16th Century and quickly began headway on building Cathedrals and Monasteries to house the new Catholic presence in the land.

Along with their patrons, the institutions built were distinctly Spanish in origin. Regardless of order, whether it be Franciscan, Dominican or Jesuit the structures still emanated the style seen across Spain’s holy buildings. Across the Atlantic ocean the spirit of Spain had made it, and embedded itself in the white walls, vaulted ceilings, and voussoirs that held up the enormous power of the Catholic church in the new world.

The sacred structures erected in South and Central America bear the flavor left on Spain by the Moores. From the outside the new Cathedrals showed resemblance to discovered Moorish forts. The infrastructure is intimidating and solid, rendered in white. Sculptural decadence varies from structure to structure. However, a striking point to note is that when the ornamentation is included it is highly geometric-in Moorish fashion. This influence snowballs into the interior as well. The alters are gilded and decadent, simple and to the point. Ornamentation is non-objective, however it is balanced and vast giving viewers plenty to work with in terms of focus points for mediation. While a new Catholic may not be staring at a Christ figure they don’t recognize, they can recognize balance and perfection within shapes.

El Laberinto: Origins

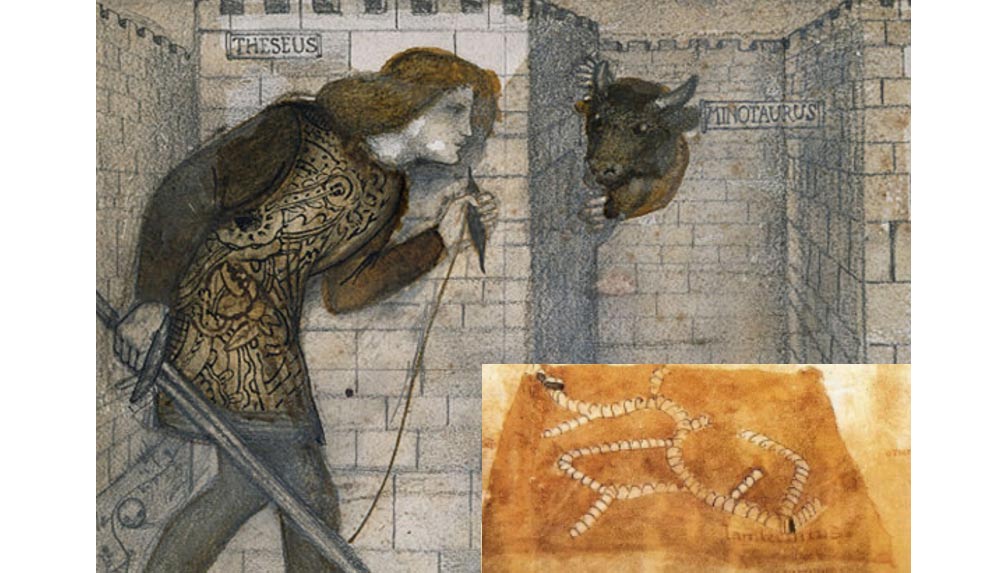

El Laberinto, or the labyrinth, holds pagan origins, and can be traced back to the Island of Crete where the Minoan people lived an arguably decadent life free of strife. The original Labyrinth is associated with the palace of Knossos and the myth goes as follows:

The craftsman Daedalus created a Labyrinth to hold the Minotaur captive. To prevent the beast from attempting to escape and wreak havoc, the Minoan people performed a sacrifice each year. Children would be sent into the Labyrinth never to return.

An Athenian hero traveled to the Island of Crete and rid the utopian town off their filicidal habits in exchange for a pardon of Athenian debts to be paid to King Minos. Entering the labyrinth under the guidance of the King’s daughter Ariadne, Theseus slays the beast.

So, what does this mean for the origins and ultimate symbolism of the labyrinth?

Unknown – “Labyrith,” Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.

It becomes a symbol of an elusive and darkly-rooted theme of playfulness and exploration. In the Cretan myth, the labyrinth acts as a tool to confuse and imprison the half-human-half-animal Minotaur. Children also cannot escape on their own. Only the already renowned ancient hero is triumphant, and even he requires help.

Ancient Spanish Monastery. North Miami Beach, FL taken by Sofia Guerra (2019)

The Labyrinth also represents the heroes’ journey, theme with a long tradition with western culture. It lives in ancient mythologies and modern religions, as well as most stories of struggle in popular culture today. The meandering maze of Crete has not been found. Its story pervades, and since its conception Labyrinths have become features to religious structures ranging in doctrine.

Pilgrimage of the Spirit

The first Cathedrals were validated by the power of the relic they held. Holy relics are often artifacts of the Saints. Catholic pilgrims made their journey to bask in the holiness of these relics they would often meditate on why they were starting this voyage in the first place. Since Cathedrals were often city centers, medieval pilgrims would travel from far and wide for their individual spiritual journey..

Similarly, to the pilgrims of medieval Europe, the spirit of exploration and spirituality of Spain made a ‘pilgrimage’ backed by militant and religious power to the New World. This sentiment came to me when reflecting upon the unknown voyage monks took, as well as the unknown exploitation the indigenous people would face upon encountering the newcomers to their land. The rapid change occurring over the megacontinent of the Americas manifested itself in violence and oppression. But in the name of God? The indigenous people had their own religious practices that the Spanish essentially dismantled upon their arrival by appropriating and changing indigenous beliefs to fit that of Catholic doctrine.

Ancient symbols such as the Labyrinth encouraged the meditative process. It is a freestanding symbol of balance and perfection: chaos perfectly enclosed in a sphere. The shape is universally recognizable. It exists in nature, and it is a common language. The sphere represents the cycle of life and death, a never-ending journey, and in this case a journey of self-exploration. It inspired the piety of pilgrims as it provided them not only the time, but a visual symbol to associate their spiritual journey with. The Labyrinth contains a meandering maze that can be conquered by few but approached by all, it exists in religions across the globe, including Hindu folklore. Today its meditative qualities are the same and still in practice.

When I began doing research for this project, I wanted to find the oldest Catholic structure in Florida. It turned out to be a 12th Century Spanish Monastery that had been completed IN Spain in 1133 and later transported to North Miami Beach, Florida in the 1950’s. Exploring this cloister led me to a labyrinth deep in the Monastery grounds that as I walked, evoked thoughts within me of the first people to walk a Labyrinth in mediation and how the symbol even came to be. It soon became clear, as the spirit of journey, self-discovery and spirituality lives within all of us, and has persisted in humans since the dawn of time.

Taken in the Monastery Gardens of the Ancient Spanish Monastery. North Miami Beach, FL. Taken by Sofia Guerra (2019).

The Spanish invasion of the Americas brought pork, sugar, disease and colonization. It also brought new religion, spirituality, and a new language for searching for spirituality. Deities range across religions but geometry exists in the natural environment that surrounds us all. Recognizing the beautiful and divine around us day to day was accentuated in this country through elaborately sculpted, geometric facades and interiors of the first Cathedrals of New Spain.

Citations:

Antonis Kotsonas. “A Cultural History of the Cretan Labyrinth: Monument and Memory from Prehistory to the Present.” American Journal of Archaeology 122, no. 3 (2018): 367. doi:10.3764/aja.122.3.0367.

Bayón, Damián, and Murillo Marx. History of South American Colonial Art and Architecture : Spanish South America and Brazil. Rizzoli, 1992.

Fiore, Jan. “A Sanctuary of Peace and Tranquility Miami’s Ancient Spanish Monastery.” Antique Shoppe Newspaper, June 2016.

Giffords, Gloria Fraser. Sanctuaries of Earth, Stone, and Light : The Churches of Northern New Spain, 1530-1821. The Southwest Center Series. University of Arizona Press, 2007.

Senn, Corelyn F. “Journeying as Religious Education: The Shaman, the Hero, the Pilgrim, and the Labyrinth Walker.” Religious Education 97, no. 2 (January 1, 2002): 124–40.

Verstique, Bernardino. FOUR. Religion in Spain on the Eve of the Conquest. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000.