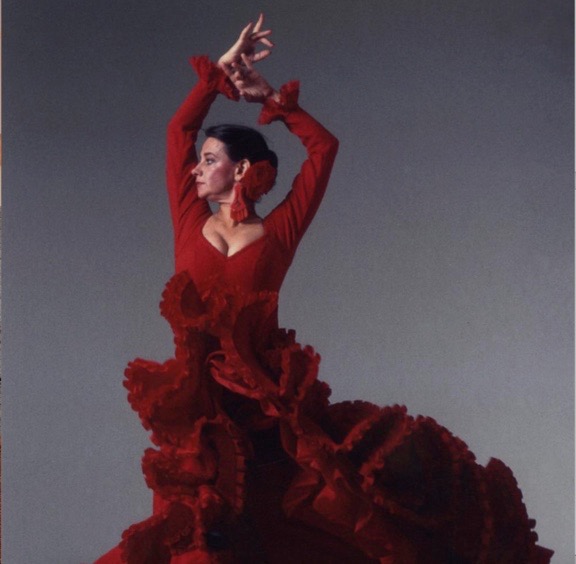

“Photograph of Carlota Santana” taken by Victor Deliso / CC by 4.0.

Flamenco is an art form which is centered around spontaneity and individuality; a pure expression of passion and emotion. It has been dubbed a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity since 2010. This is a title given to a location, collection, tradition, practice, etc., that has been passed down through generations and at the same time, evolving as time passes. It is also a symbol representative of both culture and community. This designation shows the impact that Flamenco has had on Spain, Andalucia (the heartland of Flamenco), and the artistic community. Spain nominated Flamenco to be given this honor (UNESCO, “What is Intangible Cultural Heritage”).

There are three parts to the art of flamenco: Cante (song), Baile (dance), and Toque (instruments/guitar) (UNESCO, “Flamenco”). These three elements communicate with each other in a sort of language. There are many indicators that help the performers understand when to follow one another. A subida (rise) is a series of steps a dancer will follow to indicate to the musician to speed up the rhythm of the music (Blumenfeld). Another such category of foot work are llamadas (calls), which are used by dancers for a variety of reasons, not limited to: calling in a phrase in the music, influencing when the melody comes in, starting various rhythms, etc (Hill and Chacon).

“Flamenco Dancer and Musician” photo taken from http://nspa.in/blog/exploring-the-fiery-passion-in-flamenco-dancing/ / CC by 4.0

When performing together, the dancer will choose what type of movements to make based on the type of music. The dancer will do mostly floreo (hand movements) and braceo (arm movements) when the main melody of the song or instrument is being heard, as to not distract from the music. They can also do vueltas (turns) or marcaje (marking) to outline the rhythms and mark the beats, as well as palteado (footwork) (Hill and Chacon).

There are three major types of cante (also known as palos): jondo, intermedio, and chico. The former, cante jondo, is connected to deep emotions and anguish. Cante intermedio interlaces both. The later, cante chico, is a happy and love-filled type of song. The first style is the most complex, and the complexity lowers down the list. The setting of each type of song is important, as they each represent different emotions and contexts (Bennahum). Overall, there are over 50 different song forms with varying rhythms, structure, accents, etc (Hill and Chacon). Many of these have been recently added as influences from other cultures are mixed in (Lorenz).

For the toque part of flamenco, the traditional guitar is typically used, however, other instruments, such as castanets, tambourines, and bells can be incorporated as well (Bennahum).

The unspoken communication used between the types of performers is what leads to the spontaneity of the art. Performers will often not practice with each other, but perform together by using cues from each other to work in sync. It is important for each of the performers to understand one another in order to keep on track with the rhythm. Across the globe, various Flamenco festivals, shows, conventions, etc. take place in which artists meet and perform with one another. Such is the beauty of the art; it lets artists from all over, who may not even speak the same language: dance, sing, or play together (New York Latin Culture Magazine). One such event is the yearly Flamenco Festival in New York City; it is an opportunity to meet others as well as to see the most admired flamenco artists of today. This year, 2022, marks the 20th anniversary of the festival (New York City Center).

As long as the structure is kept, in order for performers to understand each other, certain liberties can be taken in translation and execution. This is where individuality and expression come to play.

There are two general types of settings in which Flamenco takes place. One is more informal than the other professional concert-style. The former, also known as the juerga, is a more lax setting in which traditional rules and styles are more influenced by the local culture and audience. The image below shows how Flamenco dancers bring Tables (wood planks) when performing to make the proper sound with their shoes and limit injury. Traditionalist Flamenco artists relish at the juerga, as it, in a way, simulates the roots in which the art originated (Lorenz).

“Flamenco the Dance of Spain” Photo taken from https://www.spanish-living.com/flamenco-the-dance-of-spain// CC by 4.0.

The origins of Flamenco hail from the Gitanos (gypsies) in the 19th century. Living as nomads, they journeyed from Northern India to the middle east, across Europe, until settling in the Southern region of Spain named Andalucia. Across their journey, flamenco began to form into the art that it is today. The map below shows their journey. In Andalucia, it was further influenced by Moorish, Jewish, and Christian culture (Hill and Chacon). As it was an art form created by those on the lower rungs of traditional Spanish society, not much is documented on the history of the art. In addition, the Gitanos tended to pass information and customs along orally rather than in writing (Lorenz). In fact, Flamenco began as a song form with clapping hands and stomping feet as an accompaniment before the dance and instrumental aspects were incorporated (Hill and Chacon).

“Roma Gypsy Traveller’s migration pattern from the point of origin”. Graphic taken from: http://old.restlessbeings.org/projects/roma-gypsies / CC by 4.0.

Flamenco began to thrive in Spain from 1869-1910, during what is known as the Golden Age of Flamenco. Artists would play at various Cafes Cantantes (music cafes), which became popular locales in Spain at the time. These cafes are where the guitar became permanently ingrained as part of the Flamenco art. In the 1950’s, Flamenco underwent a Renaissance in which its stage migrated to theatres and concert halls. This, however, did not stop the more casual juergas, which are still a large part of the Spanish culture. Throughout this time, there were many in Spain who viewed Flamenco as an overly primitive dance. There was a movement led by majorly scholars, authors, and musicians of other genres to put a halt to the growth of Flamenco. This however, as officially marked by the integration of Flamenco as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, was pointedly not a successful movement (Spanish Living).

It was not until a century after its creation (in the 20th century) that flamenco became popularized in the Americas. In the Americas, they tend to center in on the dancing and guitar rather than the singing. In the United States, Flamenco has three major hubs in the United States: New York, San Francisco, and New Mexico. (Dumas).

New York City is the pinnacle from which Flamenco began to spread in the United States. The Zonophone Company was the first in the United States to show Flamenco in the early 1900’s. Then, Flamenco artists, such as dancer Antonia Merce, came to the United States and produced shows that people enjoyed. This led to a wave of talented artists moving here as well in order to become the first great Flamenco artists in the United States. In the 1930’s, during the Spanish Civil War, some of the most well-known Flamenco artists, such as Carmen Amaya, came to New York to flee the war (One a side note, many artists also migrated to varying other countries in Latin and South America to escape the Spanish Civil War, such as Sabicas who moved to Mexico). This ultimately was a turning point in which Flamenco culture was fully established in New York City (Dumas).

Flamenco outfits for women traditionally include a long red dress with ruffles in the skirt. Another commonplace is a flower in the hair, fans, and shawls. However, modern dancers have started to wear long, flowing gowns instead of one with ruffles in it. The image below shows an example of a modern Flamenco dress. For men, the traditional garb is a tighter, sometimes black, white, or red, outfit. Carmen Amaya, born in Barcelona in 1913, was a female flamenco dancer who broke the long-standing, traditional gender rules in terms of dress, dance style, and aggressiveness (Pennsylvania State University). As she progressed in her career, she turned towards a more feminine style of dancing. She was an honored and revered Flamenco dancer who has changed the traditional styles of Flamenco (Andalucia).

“A scene from the film “Flamenco, Flamenco”. Photo taken from: https://www.cleveland.com/musicdance/2014/03/flamenco_festival_at_cleveland.html / CC by 4.0.

One of the leading figures in popularizing Flamenco in the Americas was Jose Greco. An image of him can be seen below. Jose Greco was a charismatic dancer and choreographer. Born in Italy in 1923, he migrated to Spain for a few years, before moving to the United States. He established his own ballet company in 1945, which through he recruited prominent Flamenco figures to migrate to the United States and perform in his company. He appeared in movies as well. His son, Jose Greco III has taken over his company. His daughter, Carmela Greco, is a prominent Flamenco artist in her own right (La Prensa Texas).

“Jose Greco” Photo taken from the Centro de Documentacion De Musica / CC by 4.0.

Two renowned modern dancers are Sara Baras and Joaquin Cortes. They both currently own their own dance company and tour with them (as many other prominent Flamenco dancers have done). They both have a more flowing, graceful style: a modern approach to Flamenco. Joaquin specifically incorporates some elements of ballet, in which his original training was in. Sara Baras learned to dance Flamenco from her mother and then incorporated in her own style of expression (Andalucia). Flamenco was originally passed through generations, and it is a tradition that still stands. At the same time, anyone can now learn Flamenco through classes and videos, regardless of their nationality, language, etc.

“Amazing Flamenco Dance – Sara Baras” video posted by shahin0ne87 on YouTube / CC by 4.0.

Flamenco is seen as a generally Hispanic/white tradition. There is currently a social movement dubed “Decolonizing Flamenco”, in which black artists are gaining more recognition. They are using Flamenco as a medium of expression and acceptance. Some major pioneers in this movement are Phyllis Akinyi, Aliesha Bryan and Yinka Esi Graves. An image of Yinka Esi Graves can be seen below. They all began taking Flamenco classes in their twenties as a pastime and are all known distinguished Flamenco dancers. These three artists are dancers and although that is where this movement is beginning, there is hope that it will spread to all modalities of the art (Dixon-Gottschild).

“Yinka Esi Graves”. Photo taken by Miguel Angel Rosales / CC by 4.0

Flamenco might have originated from Andalucia, but its modern evolution has come to place due to varying influences from around the world. Cuban customs have been passed back to Spain in the form of songs, known as Ida y Vuelta palos (song forms). Another such example is the cajon, or box drum, which is a traditional Cuban instrument that has been incorporated into the art of Flamenco (New York Latin Culture Magazine). This type of cultural exchange took place across Latin and South America. Traditional songs from Argentina, Columbia, Peru, etc., have all mixed in with Flamenco to create new music or dance styles that are performed today (Bryant). Dance styles, such as jazz and hip hop have also mixed in with Flamenco to create different styles. This mix of other cultures, music styles, etc. has brought forth a new wave of Flamenco named “Nuevo Flamenco” (New Flamenco). With one quick search online, tutorials for many of these styles can be found, further mixing them together.

Flamenco is a continually evolving art. Rosalia, a Spanish mainstream singer from Barcelona, incorporates aspects of Flamenco into her music and music videos. She is revolutionizing the art and incorporating modern and urban aspects (New York Latin Culture Magazine). Modern media has been an asset to spreading the art. Beginning with movies and now social media, these modalities have been pivotal to the international acclaim and recognition of Flamenco.

What drew me to Flamenco was my love for dance in general. I grew up dancing Spanish and Middle Eastern dances. As such, having the opportunity to dive deeper into a dance that was built upon the union of multiple cultures, inspired me. Flamenco artists seek to seep their emotions into their art and communicate an un-spoken message to their audience. Looking into the future, Flamenco is a dynamic art form that is ever constantly evolving and becoming more inclusive.

Works Cited:

Arts Flamenco. “Flamenco.” Flamenco History, http://artsflamenco.org/flamenco.html.

Andalucia. “Carmen Amaya.” Andalucia.com, 26 Feb. 2021, https://www.andalucia.com/flamenco/dancers/carmenamaya.htm.

Baras, Sarah. “Amazing Flamenco Dance | Sara Baras.” YouTube, uploaded by shahin0ne87, 31 October 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QLnEjHuMFsA

Bennahum, Ninotchka Devorah. “Flamenco.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/art/flamenco.

Blumenfeld, Alice. “Flamenco is a Language.” YouTube, uploaded by TEDx Talks, 5 December 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8nQYQQcxHFo.

Bryant, Tony. “Flamenco – Styles Influenced by Flamenco.” Andalucia.com, 20 June 2014, https://www.andalucia.com/flamenco/styles-influenced.htm.

Centro de Documentacion de Musica. “Pin Su the Ballet Annual (1947-1964).” Pinterest, 7 Jan. 2017, https://www.pinterest.com/pin/367747125808422481/.

Dixon-Gottschild, Brenda. “Decolonizing Flamenco through Exploring Black Influences.” Dance Magazine, 21 Apr. 2022, https://www.dancemagazine.com/decolonizing-flamenco/.

Dumas, Anthony C.. “Flamenco (USA).” New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Oxford University Press, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2241107.

Harss, Marina, et al. “Flamenco Family Portrait.” The National Endowment for the Humanities, https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2013/julyaugust/statement/flamenco-family-portrait.

Heller. (2015). Flamenco in America: A New Film [Review of Flamenco in America: A New Film]. Dance Chronicle – Studies in Dance and the Related Arts, 38(2), 255–259. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/01472526.2015.1042952

Hill, Kristopher, and Julia Chacon. “Flamenco 101.” YouTube, uploaded by TEDx Talks, 15 March 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sCpjPWWQB3s.

La Prensa Texas. “Jose Greco – Outstanding Hispanics by Leonard Rodriguez.” La Prensa Texas, 17 Feb. 2020, https://laprensatexas.com/jose-greco/.

Lewis, Zachary. “Flamenco Festival at Cleveland Museum of Art Aims to Provide Fresh, Contemporary Experiences.” Cleveland, 4 Mar. 2014, https://www.cleveland.com/musicdance/2014/03/flamenco_festival_at_cleveland.html.

Lorenz, Roberto. “Flamenco – Its Origin and Evolution.” Timenet.org, http://timenet.org/detail.html.

New York City Center. “Flamenco Festival: New York City Center.” Flamenco Festival | New York City Center, https://www.nycitycenter.org/pdps/2021-2022/flamenco-festival/.

New York Latin Culture Magazine. “Fall in Love with Flamenco NYC. ¡Olé!” New York Latin Culture Magazine, 8 Apr. 2022, https://www.newyorklatinculture.com/culture/music/traditional/flamenco/.

NSPA.“Songs from the Streets.” NSPA, http://nspa.in/blog/exploring-the-fiery-passion-in-flamenco-dancing/.

Pennsylvania State University. “Flamenco.” The Vast World of Dance, 23 Mar. 2017, https://sites.psu.edu/mnshermanpassion/2017/03/23/flamenco/.

Rahman, Reaz, et al. “Roma Engage.” Restless Beings: Voice the Voiceless, 25 Aug. 2014, http://old.restlessbeings.org/projects/roma-gypsies.

Spanish Living. “Flamenco – the Dance of Spain.” Spanish Living, 14 Nov. 2018, https://www.spanish-living.com/flamenco-the-dance-of-spain/.

UNESCO. “Flamenco.” UNESCO, https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/flamenco-00363.

UNESCO. “What Is Intangible Cultural Heritage?” UNESCO, https://ich.unesco.org/en/what-is-intangible-heritage-00003.

“Flamenco” graphic made by Leah Daire / CC by 4.0.